As the African National Congress (ANC) prepares for its National General Council (NGC) in December, the party faces one of the most consequential moments of introspection since 1994. For party president Cyril Ramaphosa, the gathering is more than an internal review; it is a mid-term test of whether his ambitious “new dawn” reform agenda, unveiled ahead of the 2017 Nasrec Conference, has delivered tangible change for South Africans.

Since his election as ANC leader and subsequent ascent to the presidency in February 2018, Ramaphosa’s tenure has been marked by a mixture of hope, hesitation, and hard realities. His rise to the Union Buildings brought optimism about national renewal: the promise that South Africa could cleanse itself of corruption and reclaim the democratic ethos enshrined in 1994. This was at the pinnacle of South Africa’s own winter of discontent, with clamour for change. Yet seven years later, that glow has dimmed.

The December NGC comes at a time when the ANC, for the first time in its history under Ramaphosa, lost its outright electoral majority in the 2024 general election, forcing it into a 10-party coalition, named the Government of National Unity (GNU). This outcome reflects declining public confidence in the party and exposes the gap between reformist rhetoric and the political reality that has slowed transformation.

Citizens and investors now ask: Has the dawn broken, or has the darkness merely changed form?

Progress and Partial Deliveries

Ramaphosa inherited a state riddled with institutional rot. The Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture revealed sprawling networks of influence across government departments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and law enforcement agencies. Yet the deeper problem – what analysts term state capture within state capture – persists. Multiple clandestine networks operate simultaneously within institutions, often overlapping or competing, creating a labyrinth that makes meaningful accountability extremely challenging.

This layered capture is exemplified in ongoing investigations by the Madlanga Commission and Parliament’s Ad Hoc Committee, probing criminal-syndicate infiltration into the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the broader criminal justice system. On 6 July, KwaZulu-Natal Police Commissioner Lt Gen Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi held a briefing, alleging a syndicate linking politicians, senior SAPS officials, prosecutors, and even judicial officers were involved in the running of gangs, selling drugs and corruption. The disbanding of the Political Killings Task Team (PKTT) by the Minister of Police without consultation and the subsequent removal of critical evidence from the PKTT triggered the briefing by Mkhwanazi.

Testimonies thus far at both the Madlanga Commission and the Ad Hoc Committee have also highlighted intense political interference in influencing procurement and investigations, underscoring how corruption has migrated from procurement to the very agencies meant to enforce justice.

A Fragile Security Architecture

Security reform remains a persistent challenge. The 2018 High-Level Panel Report on the State Security Agency (SSA) warned of politicisation, weak coordination, and misuse of intelligence. Yet the July 2021 civil unrest, which claimed over 350 lives and caused more than R50 billion in economic losses, exposed enduring weaknesses: intelligence warnings about looting and sabotage were ignored or poorly communicated. Ramaphosa relocated the SSA to the Presidency and established a National Security Council to improve oversight, but coordination across police, intelligence, and defence structures remains inconsistent. Evidence before the Ad Hoc Committee and Madlanga Commission points to ongoing collusion between intelligence officers and organised crime. South Africa’s ability to rebuild trust depends not just on structural reform but on political courage to hold security agencies accountable.

Political Paralysis and GNU Dynamics

The ANC’s entry into a GNU has compounded internal strains. Some senior ANC leaders remain sceptical of working with the Democratic Alliance, constraining Ramaphosa’s ability to drive cross-party reform. Complicating matters further is the looming 2027 ANC leadership race, which has already begun to shape internal dynamics. Factional manoeuvring between reformists and populist blocs undermines Cabinet cohesion and slows policy implementation.

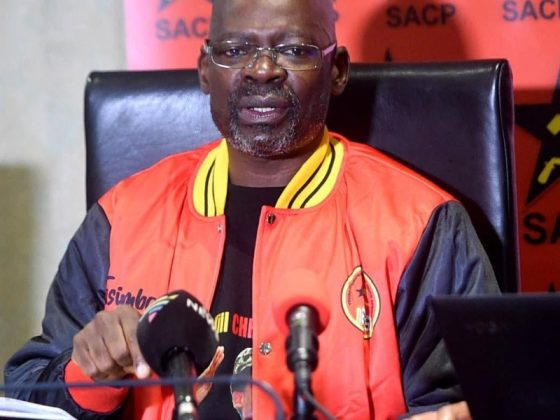

Ramaphosa’s consensus-driven leadership style, once lauded for inclusivity, now risks being perceived as indecision in an environment demanding firmness. At provincial and local levels, the disconnect is palpable. Last month, both Ramaphosa and ANC national chairperson Gwede Mantashe lamented at the Councillors’ Roll Call that lack of capacity at local-government capacity, resulting in service delivery failures was impacting the ANC’s electoral performance. The remark by Mantashe that all ANC councillors knew was signing and ‘dololo’ delivery revealed a deeper malaise: the gap between national ambition and local capability. Without alignment across ANC structures, national reforms stall, reinforcing perceptions of a fragmented government.

Institutional Reform Versus Reality

To his credit, Ramaphosa has overseen some reconstruction and recovery. Investment conferences under the 6th administration secured a cumulative R1.14 trillion in investment pledges. Following the Nugent Commission of Inquiry into SARS, the agency was restored to credibility. Boards at Eskom, Transnet, and Denel have been reconstituted; prosecutorial agencies have recovered misappropriated assets; and governance at the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has improved modestly. SAA and Eskom are back to being profit making companies. Yet accountability for state-capture crimes has been painfully slow, with many implicated officials remaining in senior roles in government or the ANC, underscoring the limits of reform within a politically cautious administration.

Professionalising the public service remains central to Ramaphosa’s agenda. The Public Administration Management Amendment Bill (PAMA Bill) that seeks to prevent public servants from conducting business with the state and Public Service Amendment Bill (PSA Bill) were passed by the National Assembly on 4 November and now await the President’s signature. Between July 2024 and August 2025, the Department of Home Affairs dismissed multiple officials for fraud, corruption, and misconduct, with eight prosecuted and sentenced.

However, more progress is still to be made. Provincial Departments of Health and Social Development faced similar cases of mismanagement. Capacity gaps and skills shortages, particularly in law enforcement, forensic auditing, and procurement oversight, slow reform implementation. Oversight bodies, including the Public Service Commission (PSC), flag staffing and budgetary constraints, limiting enforcement. Efforts to standardise performance management have yielded mixed results: while some departments report improved efficiency, others still see delays, uncoordinated planning, and failure to meet service delivery targets.

Public perception remains a barrier. Surveys show declining confidence in service delivery, particularly in local government. For citizens, reforms in recruitment and disciplinary action are less visible than inefficiencies in hospitals, schools, and municipal services, undermining trust in the state’s commitment to professionalism. Success will require sustained political will, adequate resourcing, and mechanisms to insulate bureaucrats from interference while enforcing high standards of integrity and performance.

Procedural Reform vs Transformative Change

A recurring critique of Ramaphosa’s reform agenda is that it is more procedural than transformative. Legislation has been passed, frameworks updated, and committees established, yet entrenched corruption networks often adapt faster than the institutions monitoring them. In May last year – ahead of the general elections, the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill was signed into law despite ongoing parliamentary debates and no clear implementation timeline. Similarly, the Basic Education Laws Amendment (BELA) Act was enacted under uncertainty about rollout, resourcing, and capacity. These moves, though procedurally sound, reveal a gap between legislative intent and operational readiness.

Oversight mechanisms, such as parliamentary committees and the Special Tribunal have been strengthened on paper, yet their ability to detect, investigate, and prosecute corruption is constrained by staffing shortages, political interference, and fragmented coordination. The result: progress exists in form (frameworks, commissions, and bills), but citizens’ day-to-day experiences show little tangible improvement, reinforcing perceptions that “the new dawn” remains largely aspirational.

A Bloated and Fragmented State

South Africa’s government structure compounds inefficiency. The Cabinet, comprised of 32 ministers and 43 deputy ministers, costs roughly R300 million annually, while provincial and municipal executives push total annual expenditure for political principals to just under R2 billion. This is particularly unsustainable in an economy struggling to grow.

Economic growth projections are modest: 1.1% in 2025 according to the IMF (October 2025 World Economic Outlook), 1.2% per SARB, and 1.0% from National Treasury. The heavy fiscal burden of a bloated Cabinet, coupled with overlapping departmental mandates and poor coordination, hamper service delivery and reform implementation. A streamlined executive and more coherent bureaucratic structures could release fiscal space, improve efficiency, and signal seriousness about governance to citizens and investors alike.

Economic and Social Pressures

South Africans continue to feel the strain of economic stagnation. Unemployment stands at 32.9%, with youth unemployment exceeding 60%. The cost-of-living crisis, exacerbated by rising fuel, food, and electricity prices, continues to place pressure on households. Intermittent load-shedding, though improved, disrupts domestic life and commercial activity, while crime and corruption persist, adding layers of uncertainty for business and society.

While South Africa’s delisting from the FATF grey list is a positive signal for investors, confidence remains fragile. Structural weaknesses in governance, persistent political interference, and slow reform implementation continue to undermine economic recovery. IMF, SARB, and National Treasury all warn that sustained reform is essential to unlock investment, create jobs, and stabilise public finances.

From Commissions to Convictions

For Ramaphosa’s “new dawn” to be meaningful, focus must shift from commissions and frameworks to tangible results. Commissions must yield convictions, frameworks must translate into functioning systems, and oversight mechanisms must be strengthened. Institutional credibility depends on the public perceiving that corruption is punished and that reforms improve service delivery.

The ANC’s December NGC is therefore not merely an internal party review; it is a referendum on the President’s ability to deliver on reform, uphold democratic values, and strengthen the economy. The stakes are high: the credibility of South Africa’s democratic institutions, investor confidence, and citizens’ well-being all hang in the balance.

Dawn or Dusk?

Ramaphosa’s presidency has delivered partial successes: rebuilding institutional frameworks, recovering state assets, and stabilising certain sectors. Yet transformative change remains elusive, hampered by political inertia, ANC factionalism, government fragmentation, and deep-rooted institutional weaknesses.

History will judge him not by the mess he inherited, but by whether he has the courage to confront entrenched interests, streamline government, align party structures, and implement reforms that produce tangible results. The promise of a new dawn will only be realised when South Africans see light – in accountable institutions, economic recovery, and improved living conditions. Until then, optimism of the will must contend with the stark realities of political and institutional complexity.