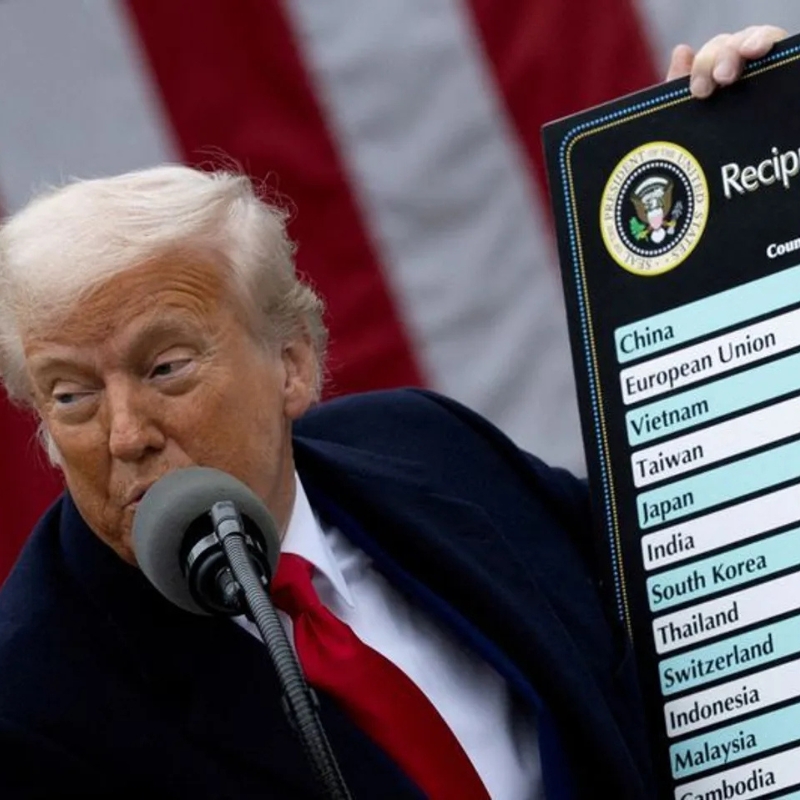

United States’ (U.S.) President Donald Trump has been back in the White House for just seven months, and during this time, he has not hesitated to fulfil some of his electoral promises, including mass deportations and addressing what he had termed the unfair trade practices on the U.S. by nearly every country that does business with the country, including some of its closest allies. Trump’s response to the unfair trade practices has seen him impose hefty tariffs ranging from 25-50% on goods exported to the U.S. from 90 countries.

Theories are abound on the logic of the high tariffs, but to make sense of them, one must look past the headlines and into his unfiltered worldview on the economy, jobs, and global trade. As unconventional as his reasoning may appear, it remains consistent, deeply rooted, and highly resistant to counterargument.

Trump’s tariff logic: jobs first

In a 15 October 2024 address to the Economic Club of Chicago, then-candidate Trump repeated his central economic creed: America cannot grow if its companies outsource jobs and still sell freely into the U.S. market. For him, this is unsustainable.

To drive home the point, Trump often recounted the story of a businessman in the auto industry who built most of his cars in plants in Mexico. Trump’s warning to him was blunt: under a Trump presidency, selling those cars in America would become “virtually impossible.” The mechanism? Tariffs – at one point, he even threatened a 2,000% tariff, which would amount to a de facto ban. In Trump’s telling, the only way companies could avoid such penalties was to bring production back to U.S. soil.

This approach extended well beyond North America. On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump railed against Europe, insisting the U.S. had been treated “very badly” in trade. He pointed to the near absence of American cars on German roads, compared with the flood of German vehicles in the U.S., and insisted that tariffs were the only fair remedy.

In short, Trump views tariffs not as technical instruments of trade policy, but as blunt tools to coerce corporations into reshoring jobs and, by extension, reviving America’s middle class.

The economic reality check

Mainstream economists, however, have long dismantled Trump’s logic.

Take his obsession with trade deficits. To Trump, a deficit means America is ‘losing’ or being ‘cheated’. One of the most prominent claims Trump made during his first term was that ‘China is paying billions in tariffs to the U.S’. This assertion was economically inaccurate, as tariffs were actually paid by American importers and, ultimately, U.S. consumers. However, by repeating this narrative, Trump was able to justify the imposition of heavy tariffs on Chinese goods, frame the trade war as a win for the U.S., despite rising costs for American businesses and consumers, and rally political support by portraying China as a primary economic adversary.

Despite evidence from economists and trade experts debunking these claims, Trump’s misinformation created a false sense of economic victory that resonated with his base.

Another cornerstone of Trump’s trade war rhetoric was the idea that the U.S. trade deficit with China is a direct threat to American economic stability. While trade imbalances exist, Trump’s narrative ignores key economic realities, such as the role of global supply chains, where U.S. companies rely on Chinese manufacturing, the benefits of cheaper imports for American consumers, and the fact that trade deficits are not inherently damaging but rather a natural result of consumer-driven economies.

By simplifying and distorting the issue, Trump was able to stoke fears that America was being “ripped off” by China, thus justifying aggressive trade policies. By leveraging misinformation, Trump has positioned China as the scapegoat for deep-seated economic issues, distracting from the need for internal policy reforms.

As renowned economist Jeffrey Sachs and others argue, the deficit reflects the U.S. economy’s structural imbalance: Americans consume more than they produce, while national savings remain low. Tariffs cannot solve this.

Even if they could, the payoff in jobs would be marginal. A Harvard study, which examined the relationship between trade balances and manufacturing employment, concluded that achieving a trade surplus or reducing the trade deficit would have a minimal impact on the share of manufacturing employment in the U.S. economy. It further posited that eliminating the deficit would raise manufacturing employment only from 8% to perhaps 10% – far from the manufacturing renaissance Trump envisions. The study found that factors such as automation and productivity growth, play a more significant role in determining manufacturing employment levels.

Moreover, evidence shows that companies have largely absorbed tariffs in two ways: by passing the costs on to consumers or by shifting production to third countries such as Vietnam or Mexico. Only a fraction have returned operations to the United States. The result has been higher consumer prices, not an industrial revival.

When economics meets geopolitics

Still, Trump has remained unmoved by counterarguments. His tariffs are best understood less as rational economic policy and more as instruments of conviction, grounded in his belief that reshoring is essential to U.S. prosperity.

Yet economics is not the whole story. Secondary geopolitical calculations are often at play. Take South Africa: some analysts linked tariffs on South African goods to Trump’s rhetoric on “white genocide.” But in fact, they align more closely with his fixation on trade balances. At the same time, Washington does have strategic interests in South Africa, particularly the Cape of Good Hope’s sea route. With Red Sea shipping disrupted by Houthi attacks, maritime traffic has surged around the Cape, elevating the region’s importance for both the U.S. and Israel. Tariffs, in this context, provide leverage.

Brazil provides another case study. There, Trump wielded tariff threats not only to advance trade goals but also to pressure the government into dropping charges against former President Jair Bolsonaro – a clear example of tariffs as geopolitical coercion.

Two things can be true

The Trump tariffs, then, serve dual purposes. Primarily, they stem from Trump’s idiosyncratic economic nationalism: the conviction that tariffs can force companies to move their manufacturing to the U.S. and restore American jobs. But secondarily, they function as bargaining chips, flexible tools of foreign policy to extract political concessions.

Two things can therefore be true at once: the tariffs are rooted in Trump’s economic worldview, but their application also extends into the geopolitical arena.