The Tripartite Alliance, made up of the African National Congress (ANC), Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), and the South African Communist Party (SACP) has long served as the bedrock of South Africa’s post-apartheid political landscape, united in pursuit of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR). As the 2026 local government elections (LGE) loom, COSATU finds itself stuck between its historical loyalty to the ANC and its ideological affinity to the SACP, after the latter resolved to contest the 2026 LGE independently. During its recent meeting with the ANC on 20 October, COSATU sought to play the role of a unifier by reaffirming the “deep bonds of comradeship” shared by alliance and the South African National Civic Organisation (SANCO), rooted in the struggle against apartheid.

COSATU’s Dilemma

The decision by the SACP to contest the elections independently, has no doubt created a dilemma for COSATU. Whilst the labour federation is unhappy with the ANC’s policy decisions and the formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU) with the Democratic Alliance (DA), abandoning a party that is in government and still has significant policy influence is not a viable option at the moment. Although the SACP is ideologically more aligned to COSATU, backing it over the ANC carries some risks. Thus far, the SACP has failed in all the by-elections it has contested. The SACP simply does not have the machinery nor resources to adequately compete on the ground. COSATU could provide the machinery, but resources will still be an issue.

The SACP is also not as strong a brand as the ANC in communities, despite its history. The ANC boasts a massive membership base with over a million members versus the SACP’s membership which is significantly smaller at 340 000 members and has declined amid internal debates and overlapping dual memberships with the ANC. The SACP’s encouragement that members also hold ANC membership has further diluted its independent identity. This disparity underscores the ANC’s entrenched grassroots network versus the SACP’s reliance on alliance structures for visibility.

Should COSATU take the risk?

COSATU has been unhappy with its relationship with the ANC for a while now and even though some of its leaders may personally benefit from being tied to the ANC, the greater labour movement has suffered from the association. COSATU’s entanglement with the ANC has diluted its independence, making it appear as an “ANC proxy” rather than a workers’ advocate, this has resulted in eroded trust among rank-and-file workers.

Consequently, COSATU’s membership has declined from a peak of 2.2 million in 2012 to approximately 1.5 million by 2024, a loss of over 700,000 members. This decline accelerated post 2015, with 416,000 members lost by 2022 alone, exacerbated by the expulsion of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) in 2014 over its refusal to back the ANC electorally. The ANC’s corruption, state capture under Jacob Zuma) and policy betrayals have tarnished COSATU by proxy. Political analyst commentator Sanet Solomon notes that the alliance has made COSATU “irrelevant”, with workers losing faith in the federation.

COSATU’s frustration with the ANC is not only about policy but also about process and consultation. The formation of the GNU in 2024, following the ANC’s loss of its outright majority, was a major turning point. COSATU and SACP publicly criticised the ANC leadership for excluding alliance partners from meaningful input into coalition negotiations and cabinet appointments. This lack of consultation reflects a long-standing pattern where alliance partners are treated as electoral assets rather than policy equals.

The core strategic question now confronting COSATU is whether to remain within a strained alliance for pragmatic influence or pursue a new political alignment with the SACP based on ideological renewal. The risk of departure is enormous as breaking away from the ANC could isolate COSATU politically, reduce its policy leverage, and expose it to resource shortages. However, remaining tethered to a weakened ANC could further erode its legitimacy among workers.

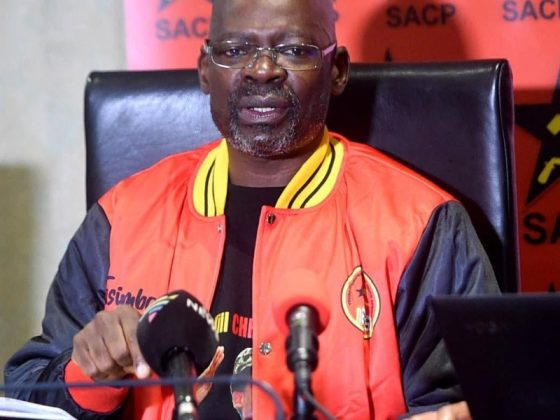

On the other hand, publicly backing the SACP’s decision carries some risks for COSATU. It seems the decision to go at it alone in the upcoming elections does not enjoy everyone’s support within the SACP. SACP’s National Chairperson Blade Nzimande has proposed convening a Special National Congress to review and reassess the party’s decision. In a discussion document released early November Nzimande highlighted implementation challenges since making this decision, including poor internal communication which has led to confusion among members with dual ANC-SACP membership and inadequate analysis on the actual situation.

In the short term, a gradual realignment may be more viable than a full break. COSATU could explore a dual-track strategy, maintaining formal ties with the ANC while supporting SACP-led campaigns on specific issues like public sector wages, industrial policy, and social security reform. This would allow the federation to rebuild its grassroots legitimacy while preserving access to government influence.

What is at stake for the tripartite alliance?

The Tripartite Alliance’s fragmentation would represent a historic rupture in South Africa’s political landscape. For three decades, it has been the ideological anchor of post-apartheid governance, shaping economic transformation, labour law, and social welfare policy. Its breakdown could lead to a weakened ANC, facing electoral decline, a fragmented labour movement, further diluting worker power, policy incoherence, as the historical alignment between social justice, state power, and organised labour dissolves, and a shift in political identity, as the working class seeks alternative streams of representation.

If COSATU and the SACP were to pursue the building of a broader “Popular Left Front”, uniting other progressive movements outside of the ANC, as suggested by Nzimande, it could reshape South Africa’s left politics and challenge the ANC’s monopoly over liberation credentials. Yet, the success of such a realignment would depend on the ability to mobilise workers beyond rhetoric, create sustainable funding mechanisms, and develop a coherent policy alternative to the ANC’s centrist governance.

Conclusion

With the future of the Tripartite Alliance in the balance, COSATU stands at a crossroads between political loyalty and ideological authenticity. Remaining within the alliance may secure short-term influence but deepen long-term irrelevance, while aligning with the SACP may revive ideological clarity but risk political marginalisation.

Ultimately, the survival of the alliance depends on whether its partners can redefine the NDR for a new generation, one grappling with youth unemployment, inequality, and declining trust in liberation-era politics. Without renewal, the alliance risks becoming a relic of history rather than a driver of transformation.